How a closer look at the rise of alternative investments may help expand your clients’ portfolios.

October 7, 2024 – Simply defined, alternative investments refer to any asset class that falls outside the parameters of traditional investments like stocks, bonds and cash-related instruments. Under this broad umbrella, alternatives may include tangible assets like residential and commercial real estate, infrastructure, natural resources, precious metals and other commodities, as well as collectibles like art, antiques, stamps, coins, digital assets — and even rare whiskey.

Alternatives also comprise financial instruments like hedge funds, derivatives, private equity, private credit, venture capital, carbon credits and managed futures. The commonality that unites all these investments is their ability to diversify investor portfolios with an asset class that historically has lower correlation to traditional investments.

Historically speaking, the earliest alternatives were only accessible to institutional investors like pensions and university endowments, as well as high-net-worth investors. But as the evolution of alternatives continues, so does their reach.

This article shines a light on the history of alternatives and telegraphs what lies ahead. The second in a three-part series, it follows The Basics of Alternative Investments and precedes a forthcoming article exploring key misperceptions about alternatives.

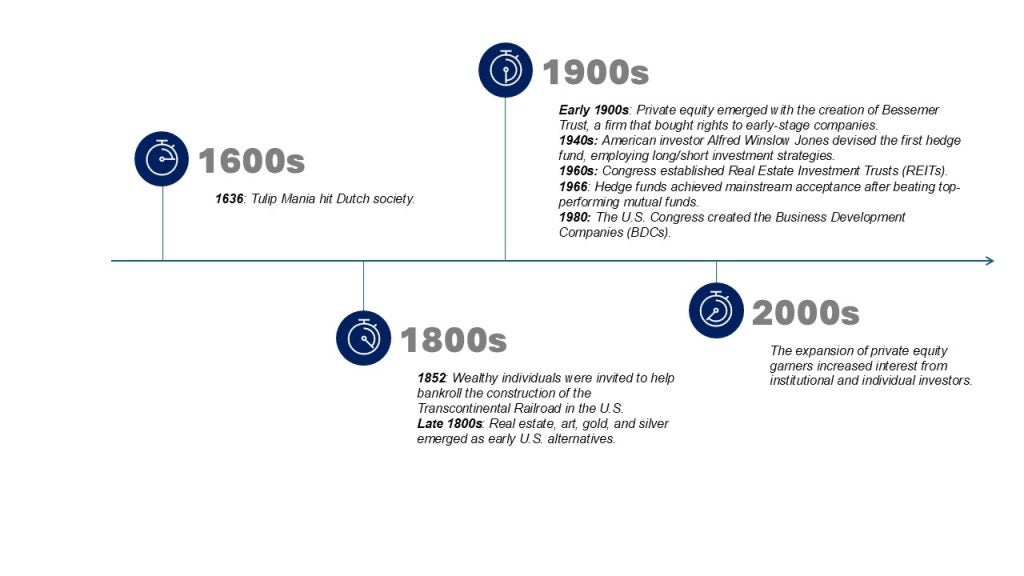

The History of Alternative Investments Timeline

When Alternatives Began

There is much debate about exactly how and when the very first alternative investment surfaced. After all, private art sales date back to Roman times, while the Stockholm Auction House, the world’s first of its kind, opened its doors in 1674. And who could forget Tulip Mania, the mid-1600s Dutch craze where rare flower bulbs were traded for up to six times the average person’s annual income?

In the U.S., one of the most significant early alternative investments emerged in 1852, when investors were able to help finance the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad.1 Due to structural limitations by banks in that era, wealthy families were invited to pair their private capital with government bonds to bankroll this massive undertaking, which took six years to complete, spanned 1,911 miles, and linked the eastern and western shores for the first time. More importantly, it opened the door for direct investments in the improvement of roads, bridges and other critical infrastructure in the latter 1900s. Farmland, gold, and other precious metal commodities were also targeted as alternatives to traditional stocks and bonds.

Hedge Funds: The Original Game Changers

Nothing changed the alternative investment landscape quite like the 1949 introduction of the first hedge fund. The brainchild of American investor Alfred Winslow Jones, this pooled vehicle had the ability to employ a long/short strategy of buying stocks expected to rise in price while simultaneously short-selling stocks poised to decline — a one-two punch aimed at reducing market volatility in the fund. This fund also pioneered the then-unique fee structure, where accredited investors paid a 2% management fee of the fund’s net asset value, on top of an annual 20% performance fee, due to the active management style involved.

While hedge funds were initially slow to catch on beyond a small circle of investors, that changed when a 1966 Fortune magazine article revealed how Jones’ fund handily outperformed every other mutual fund over the five years prior — beating the most successful one by a whopping 44%. Two years later, some 140 new funds hit the market.2 Today, there are approximately $5.15 trillion in hedge fund assets.3

The Broader Alternative Investment Universe

While the rise of hedge funds was a key driver in advancing the alternative investment phenomenon, other notable alternative asset classes have also made their marks. These include:

Private Equity: Private equity refers to any investment capital used to acquire stakes in private companies or, alternatively, to seize control of public companies with the intent to delist them from stock exchanges. Private equity firms launch funds that serve as general partners (GPs), while the funds’ investors — typically pension funds, insurers, sovereign wealth funds, or high-net-worth individuals, function as limited partners (LPs). Over time, the GPs own and manage the portfolio of companies, with an eye toward improving the financial outlook and operational efficiency to sell them, ideally for a gain, in an acquisition deal or to list them on an exchange.

The private equity deal harkens back to the turn of the 20th century when J.P. Morgan purchased Carnegie Steel Co. from Andrew Carnegie and Henry Phipps — the latter of whom used his share to create Bessemer Trust, which bought rights to up-and-coming companies. In later years, private equity widened its embrace to invest in established companies — often in financial distress. And today, private equity investments can target companies in various life cycle stages. They may range from pre-seeded companies in the early stages of product development all the way to buyout/recapitalization-oriented companies boasting revenues of $10 million or more.

Despite a decline in private equity deals in 2023 — largely the consequence of rising interest rates depressing fundraising efforts — the long-term outlook in this asset class seems to be strong. This year, seven of the largest private equity firms reported a collective $722 billion in “dry powder” as of June 30th, which is a 9% increase from last year.4 Dry powder is money raised by private equity fund managers that has yet to be deployed.

Venture Capital: A subset of private equity, this investment structure occurs when fund managers invest capital in start-ups in exchange for equity — and sometimes board seats. Venture capital firms often provide technical and management expertise to help companies tilt towards profitability in anticipation of going public or becoming acquired. Venture capital experienced a boom in the 1980s with the rise of personal computers but experienced a slow-down following the 2000 dot-com bubble burst when many tech companies folded. But in the second quarter of 2024, global venture capital funding climbed 5% quarter over quarter, reaching $94 billion in 4,500 deals.5

Business Development Companies (BDCs): Created by the U.S. Congress in 1980 as an amendment to the Investment Company Act of 1940, a Business Development Company is a type of unregistered closed-end investment vehicle that invests in small and mid-sized enterprises. This legislation was enacted to stimulate growth in businesses by enabling private equity funds to access public markets to infuse them with needed capital. BDCs are strictly mandated to invest at least 70% of their assets in non-public companies with market values under $250 million. BDCs present tax-advantaged opportunities, since they are not taxed at the corporate level, as long as at least 90% of a BDC’s income is distributed to investors. Moreover, BDCs offer alternative investors the potential for income and diversification away from traditional stocks and bonds.

REITs: Established by Congress in 1960, Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) provided access to individual investors to invest in large-scale real estate like corporate offices, warehouses, shopping malls, medical facilities, storage units and apartment complexes. Similar to BDCs, REITs offer investors tax efficiencies because they aren’t subject to corporate income taxes and returns on capital distributions may be partially tax deferred. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 further stimulated an increase in the interest of REITs by allowing them to manage real estate in addition to solely owning or financing it. Today, U.S. REITs claim over $4 trillion of gross real estate with public REITs accounting for $2.5 trillion in assets.6

Alternatives: A Look Ahead

The alternative investment industry has continued to flourish over the years, with current assets under management at all-time highs. Together, alternatives represent a whopping 15% of all global investments — some $22 trillion in assets. And while this is a quantum leap from $4.8 trillion just 20 years ago, their numbers are projected to continue climbing to potentially reach $24.5 trillion by 2028.7,8

For additional information on how alternatives have evolved over the years, visit our previous article: The New Era of Alternative Investments.

Managing Risk

1 Catherine Cote, “The Future of the Alternative Investments Industry,” Harvard Business School Online, Aug. 31, 2021.

2 “A Brief History of Hedge Funds,” The Repool Blog, Sept. 22, 2022.

3 “Hedge Fund Industry,” BarclayHedge, accessed July 24, 2024.

4 “Private Equity Builds $722B War Chest in Hunt for Deals,” Mergers & Acquisitions, Aug. 8, 2024.

5 “Venture Capital Growth to Remain Solid Despite Headwinds,” Preqin Global Report, Dec.14, 2022.

6 “REITs by the Numbers,” Nareit, accessed July 24, 2024.

7 Varon Filbeck, “The Next $20 Trillion in Alternative Investments,” CAIA, Jan. 2024.

8 Steve Randall, “Global alternatives market set to reach $24.5T, private credit AUM to double,” Investment News, Oct. 19, 2023.

Represents CNL’s view of the current market environment as of the date appearing in this material only. There can be no assurance that any CNL investment will achieve its objectives or avoid substantial losses. Diversification does not guarantee a profit nor protect against losses.

CSC-0924-3805052-INV-E